Influenza A Virus Infection and Innate Immunity in Young Children

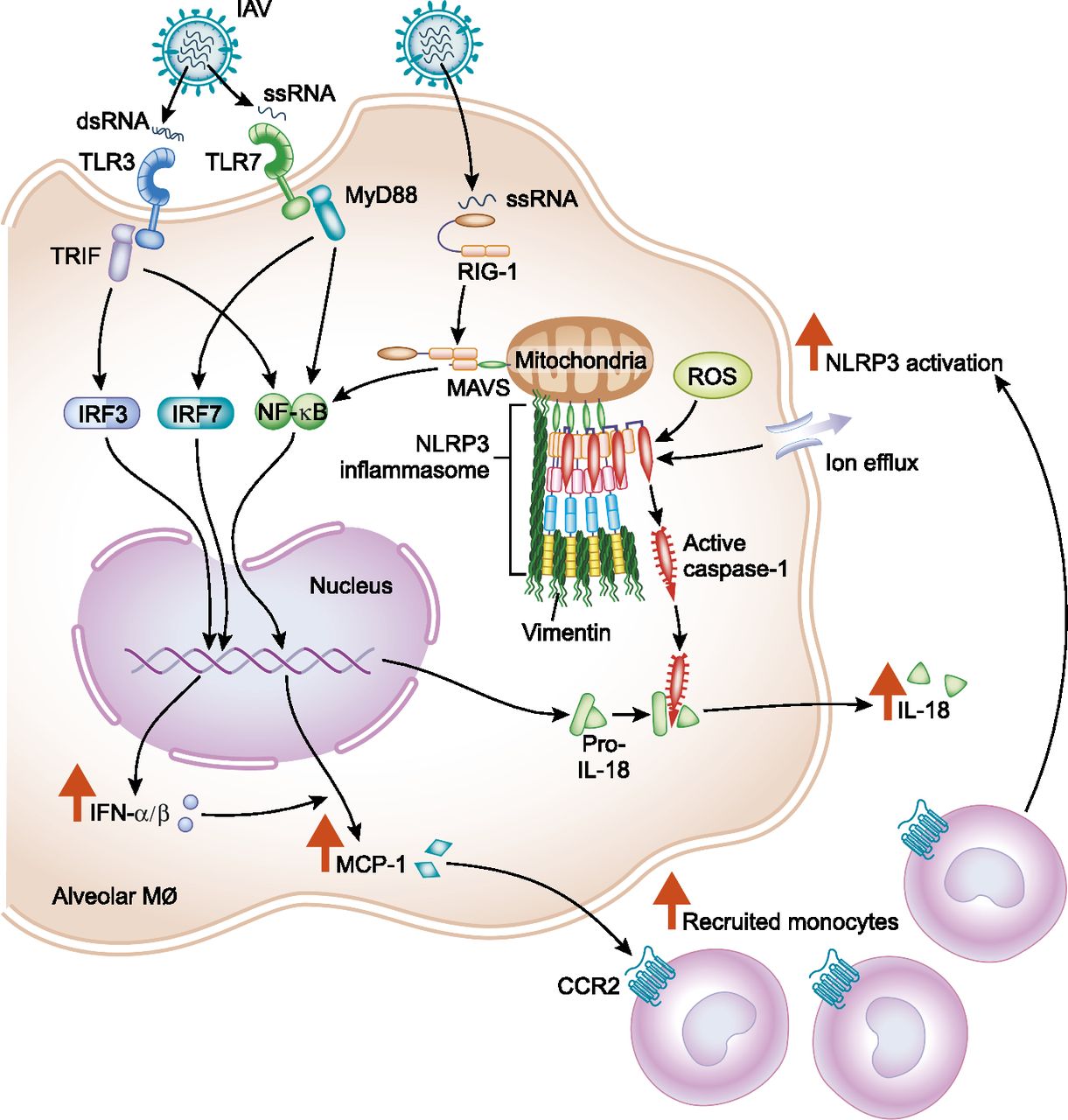

Diagram showing how the juvenile innate immune response to influenza A virus (IAV) predisposes children to IAV-induced lung injury. From Coates et al. 2018.

Influenza A virus (IAV) is a highly contagious single-stranded RNA virus that is responsible for 3–5 million cases of severe infection and up to 650,000 deaths annually worldwide. The burden of IAV infection is greatest among children, the elderly, and persons with chronic medical conditions [1]. Each year, up to 40% of the pediatric population younger than 5 years in the United States will contract influenza [2]. Young children who develop lower respiratory tract IAV infection are at risk of severe, life-threatening disease.

Underlying medical conditions such as asthma or premature birth place certain children at increased risk of severe IAV infection, but these conditions account for only 50–60% of cases. The remaining cases occur in previously healthy children with no predisposing medical conditions. In contrast, predisposing risk factors such as chronic medical conditions or advanced age account for almost all of the morbidity and mortality of influenza among adults [3].

Why healthy children are much more likely to contract severe, life-threatening IAV infection than are healthy adults is unclear. Anatomical factors and immature immune systems contribute to the increased vulnerability of young children to IAV infection, but they do not adequately explain the susceptibility to severe disease observed in this population [4].

To investigate the differences between adults and children in the host response to IAV infection, we have developed a mouse model of pediatric influenza using 4-week-old juvenile mice infected with the mouse-adapted IAV strain A/WSN/1933(H1N1). As with humans, juvenile mice infected with IAV have increased morbidity and mortality compared with adult mice [5].

Both adult and juvenile mice showed similar levels of viral clearance, indicating that higher viral titers do not account for the increased disease severity seen in juvenile mice. Instead, this increase is associated with elevated production of the inflammatory cytokine IL-18, upregulated and sustained production of MCP-1, and an increase in the recruitment of inflammatory monocytes to the lungs in juvenile mice [6].

We have found that inhibition of monocyte recruitment by treatment with an anti-CCR2 antibody improved survival and decreased inflammatory lung injury in juvenile mice infected with IAV [6]. We also found that treatment of IAV-infected juvenile mice with the compound MCC950, which reduces IL-18 production by inhibiting the NLRP3 inflammasome, resulted in decreased mortality, reduced lung injury, and attenuated secretion of IL-18 [5].

These findings will improve our understanding of the innate immune response in children, and will help us develop targeted therapeutic strategies and improved vaccines for the pediatric population.

- World Health Organization, Influenza (seasonal) fact sheet, http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs211/en/ (accessed January 25, 2018).

- Pickering LK, et al., eds. Influenza. Red Book: 2012 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 29th ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2012. pp. 439-53.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, FluView: Influenza hospitalization surveillance network, http://gis.cdc.gov/grasp/fluview/FluHospChars.html (accessed January 25, 2018).

- Coates et al., Influenza A virus infection, innate immunity, and childhood, JAMA Pediatr, 2015 (PMID: 26237589).

- Coates et al., Inhibition of the NOD-like receptor protein 3 inflammasome is protective in juvenile influenza A virus infection, Front Immunol, 2017 (PMID: 28740490).

- Coates et al., Inflammatory monocytes drive influenza A virus-mediated lung injury in juvenile mice, J Immunol, 2018 (PMID: 29445006).